Abstract

Corridors are promoted as seamless solutions for economic development, integrating production and consumption networks. However, they often fall short, fail, and operate as tools of accumulation for some while unevenly and, at times, violently reshaping the lives of others. This paper examines how corridors are constructed through dialectical processes of enclosure and opening, involving the enclosure of land, livelihoods, and social relations alongside the opening of spaces for speculation and accumulation, which we argue constitute corridorisation. Central to this process is abstraction, which transforms corridors into commodities, obscuring inherent contradictions and violence. Drawing on Marx’s concept of commodity fetishism, we analyse corridors in Indonesia and Laos to trace the processes and effects of corridorisation. By exposing the fetishisation of corridors, this paper unmasks the hidden social relations and uneven impacts underpinning their development, shedding light on who and what is excluded from these visions of progress.

Introduction

Corridors mark a return to infrastructure-led development and spatial planning, following an era of aspatial and ahistorical development policies initiated by the Washington Consensus (Gore 2000). Development or economic corridors are strategically conceived geographic regions designated for connectivity and investment, primarily through establishing infrastructure like railways or roads to enhance trade, regional connectivity, agricultural output, or access to natural resources, with the goal of integrating urban and hinterland areas. The rhetoric surrounding corridors portrays them as indispensable for progress, growth, and at times, security. Although governments, multinational corporations, and international financial institutions champion development corridors as a panacea for economic challenges, this advocacy often aligns with their own economic agendas and profit motives.

The global proliferation of development corridors is, thus, entwined with the broader dynamics of global capitalism, which increasingly approaches development goals through the logics of private capital (Taggart and Power 2024). Corridors are positioned as a potential solution to a central contradiction of capitalism that Marx (1978) identified in Capital, Volume II. While Marx initially focused on contradictions at sites of production like labour exploitation to maximise surplus value, he later examined the circulation and realisation of value, attending to the potential crises that arise during these processes, such as the inability to sell already produced goods on the market. Development corridors offer a bundle of policies and projects aimed at overcoming these circulation challenges and contradictions. However, scholars have critiqued the rise of spatial planning development policies, noting disjunctures between how corridors are conceived and how they materialise (Enns and Bersaglio 2020; Grant 2024; Murton and Lord 2020; Rippa 2020b). They often escape the control of planners due to their scalar and spatial distance (Schindler and Kanai 2021), producing unexpected social, economic, and political effects (Dwyer 2020; Lesutis 2020, 2022) and causing the very idea of seamless integration and economic growth to unravel (Jenss 2023; Zajontz 2022). Murton and Narins (2024) challenge narratives about corridors’ economic and logistical potential through their conceptualisation of chokepoints. Through their analysis of corridors in Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Nepal, and Myanmar, they highlight that, for many who live with and through these projects, the experience is not strictly one of enhanced connectivity but rather of encountering chokepoints that impede promised benefits.

This paper provides further empirical evidence of the disconnect between the intent of development corridors and their manifestation through our conceptualisation of corridorisation—the material and discursive processes that make corridors and their less visible disruptions possible. We conceptualise corridorisation as an iterative, dialectical process characterised by ongoing cycles of enclosure and opening, underpinned by forms of abstraction that create the corridor as a commodity. Centrally, corridorisation requires the enclosure of land, livelihoods, and social relations to enable future investment. These enclosures are obscured as corridors are fetishised as a commodity to render it legible for certain types of investment and speculation, leading to uneven capitalist development. Marx’s concept of commodity fetishism illuminates how these processes of obfuscation enable development corridors to be bought and sold as commodities while concealing the inherently incomplete nature and uneven effects of corridorisation.

We draw on extensive fieldwork conducted between 2017 and 2024 in Indonesia and Laos along the Jakarta–Bandung Railway and the Laos–China Railway. Both projects intend to facilitate movement and economic growth and involve significant Chinese investment, with strong domestic state support. As part of wider infrastructure-led development initiatives to enhance regional connectivity, investment, and capital accumulation, economic corridors have coalesced around these major railway projects. The Jakarta–Bandung Corridor, which emerged through substantial private investments in housing developments, new towns, and industrial estates (Firman 2009), is being reshaped by its integration into megaregion urbanisation initiatives led by Indonesia’s central government to further integrate urban areas throughout Java (Hudalah et al. 2024). In contrast, the Laos–China Corridor traverses primarily rural and peri-urban areas and has roots in several state-led and regional initiatives, including the 1995 proposal of the Singapore–Kunming Rail Link and Yunnan’s 2008 North Plan. However, it was not until after railway construction began as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that the two governments agreed to develop the Laos–China Economic Corridor in 2019. In each corridor, we undertook interviews and ethnographic observation with residents, local officials, planning professionals, and government employees from various agencies. Additionally, we analysed project documents detailing developmental visions and operational logistics, such as land expropriation and valuation. We compare variegated effects on villagers, the unequal impacts of construction, and the power of the commodity fetish that facilitates the continued reproduction of corridors as a development solution.

To theorise and examine corridorisation, the article is structured as follows. We begin by conceptualising corridorisation as a dialectical process of commodification, focusing on two central dynamics: the interplay between enclosure and opening as it reconfigures space and lives and the role of abstraction and fetishisation within enclosure and opening. As development is an open-ended process influenced by various forces, so the closure-opening dialectic is not necessarily teleological or linear. However, we first examine forms of enclosure followed by corridor opening to clarify how these processes relationally operate. The following section empirically details three forms of enclosure that enable corridor development: that of land, social relations, and labour and livelihoods. Building on this, we examine how dynamics of commodification and abstraction, which initially facilitated enclosure, subsequently function to “open” the corridor to investment by making it legible for speculation. Through this analysis, we demonstrate that the dialectic of enclosure and opening produces a commodity fetish that effectively masks the lived experiences of those outside the marketed development visions that attract corridor investment. By examining the corridor as a fetishised commodity, we foreground the perpetually incomplete nature of corridorisation and its uneven, at times violent, effects.

Corridorisation, Commodification, and the Dialectics of Enclosure and Opening

Development corridors are large-scale infrastructural initiatives designed to facilitate the movement of select people, capital, things, and investments motivated by visions of hyperconnectivity. These projects integrate dynamics of production, logistics, and commerce (Lesutis 2020; see also Enns 2018), aiming to trigger economic linkages and benefits for typically peripheral places through investment and cross-sector multiplier effects (Scholvin 2021). Although corridors are often presented as innovative solutions, they have a history dating to the 1960s and 1970s and continue to be implemented globally. Materially, corridors create and link vast infrastructure networks—like roads, railways, ports, and special economic zones—designed to stimulate the economy and boost economic growth by connecting distant areas into cohesive economic regions. Murton and Lord (2020:2) characterise corridors as “strategic spaces of passage and infrastructural assemblage”, where hyper-mobility, cross-border commerce, and cascading economic benefits intersect with various forms of power. For instance, corridors become complex spaces of negotiation between international and local actors (Abb 2023) and, like other forms of infrastructure-led development, rely on promises of future benefits (Anand et al. 2018).

Corridors emerge within specific historical and geopolitical contexts, often shaped by legacies of colonialism (Aalders 2021), bilateral relations and diplomacy (Abb 2023), and local development and political agendas. Present discourses surrounding corridors tend to emphasise the market and private sector involvement—forces often framed as “new” and “transformative” despite their roots in colonial logics and practices (Enns and Bersaglio 2020). Aalders’ (2021) study of Kenya’s LAPSSET corridor highlights the continuity between British colonial-era state control and capital accumulation and contemporary rationales for corridor and railway development. For Aalders, the LAPSSET corridor is not merely a response to Kenya’s present needs but a vision for a future, modernised Kenya that promises economic development for those living along the corridor.

Within the corridors we study, residents hold a range of, at times, contradictory perspectives on the promises and pitfalls of corridor and infrastructure development, revealing simultaneous hope and concern (DiCarlo 2025; Taij forthcoming). While recognising the potential benefits of infrastructure connectivity and economic opportunities for remote or historically marginalised “frontier” regions, we argue that understanding the limitations and failures of corridors requires examining less visible and unforeseen aspects of their development, particularly if the goal is to create multiplier effects for hinterland or “disconnected” areas. Like Grant (2024), we focus on domestic corridor dynamics rather than the “usual subjects of corridor study—international routes and boundary sites”, with an interest in the construction of abstract development space and its effects for everyday people.

This article contributes to scholarship on the uneven development of corridors by building on recent research examining corridors and corridorisation (Grant 2024; Mayer and Zhang 2021; Rippa 2020a; Zajontz 2022). Much of the literature on corridors focuses on their role in facilitating connection and exchange. Extending this, Rippa (2020a) demonstrates how corridors act as forms of containment and control, theorising “corridor-isation” as both facilitating trade and enabling the integration of illicit practices into state-sanctioned businesses. Additionally, corridors have bypassed local forms of trade and negatively impacted traders (Rippa 2020b). Broader research on economic corridors also addresses neoliberal development models, territorialisation, and power dynamics, tending to examine results and drivers while saying less about the processes and their related effects that bring a corridor space into being. However, processes of making and unmaking the corridor are critical because, as Zajontz (2022) points out, seamless corridor visions are contested in ways that engender processes of de- and re-territorialisation. We argue that the material and discursive processes of creating these spaces deserve closer attention alongside corridor effects.

Drawing on critical development studies and Marxian political economy, we propose a framework for understanding processes of corridorisation by theorising several inherent tensions. One key tension is the dialectic of enclosure and opening. Corridorisation simultaneously encloses space while opening it to certain forms of capital or “development”, reconfiguring spaces and relations to be contained and replaced by others that centre accumulation. This transformation operates as a technology of enclosure, simplifying complex socio-spatialities, often for state control (Rippa 2020a). By flattening the socio-spatial landscape of regions, corridors enable greater state oversight of the spaces they traverse and the activities occurring within them. This mechanism mirrors historical processes along the lines of the English Enclosure Acts, which Marx identified as a necessary precursor for capitalism’s expansion (see also Thompson 1975). Forms of enclosure have evolved through changing political economies, migration, and investment (Peluso and Lund 2011). Enclosure, in the context of corridor development, is a contemporary tool that supports the “infrastructural land rush” (DiCarlo and Sims 2023), facilitating the enclosure of land, resources, and populations, ultimately serving the interests of the state and capital. However, the relationship between enclosure and opening is not linear; these processes dynamically interact depending on how enclosure occurs and how corridor legibility shifts over time. For instance, processes of encouraging speculative investment in corridors can precede the physical enclosure of space. While the creation of a corridor depends on enclosure, this enclosure is often incomplete, which can hinder the realisation of the corridor’s promised potential.

Furthermore, corridorisation occurs through the abstraction and fetishisation of the tensions between enclosure and opening. Like Marx’s concept of commodity fetishism, which obscures the labour relations behind the production of goods, the creation of corridors involves the commodification of space, obscuring existing socio-spatial relations. As Marx (1976:167) wrote, value “does not have its description branded on its forehead; it rather transforms every product of labour into a social hieroglyphic”. Fetishisation points to how social and labour relations that produce commodities are obscured and displaced. Even before their material realisation, corridors are commodified with the expectation of speculative development and investment. Kaika and Swyngedouw (2002) argue that modern urban infrastructure, like water and waste systems, became commodities that generated a fetish of urban modernity, obscuring the environmental and social relations they entailed. Similarly, the corridor fetish contributes to its global proliferation as a development tool that promises regional and local economic growth. As such, abstraction obscures complex social, political, and economic realities, presenting corridors as unambiguous drivers of development. Meanwhile, fetishisation reveals the untenable production of the corridor as a commodity, which fails to deliver on promises of transformational futures due to their reliance on incomplete and often violent processes. Yet, much like development as an industry, failure begets further investment and interventions.

A further tension arises between the use value and exchange value of corridors. Use values include increased connectivity, transportation networks, energy grids, and communication infrastructure within and between regions designed to facilitate the movement of goods, services, and people as corridors promote production, trade, mobility, and market integration. In contrast, the exchange value of corridors is tied to their role as catalysts for speculative development, as business interests and developers see them as opportunities for profit. This tension reflects Yunita et al.’s (2023:2273) argument that sustainable development projects are constructed to be legible to private investors such that “what undergirds market development for green and SDG [Sustainable Development Goal] bonds is not so much an innovative endeavour as a recursive iteration of a high-modernist, technocratic-capitalist mode of seeing and doing development: to see and act on the SDGs as an investable proposition”, ultimately inadequately integrating the social costs involved. Similarly, the idealisation of smooth corridor space abstracts the messy, incomplete socio-spatial processes of enclosure and opening that are frequently incompatible with the everyday lives of people in these spaces and the “development” they are promised.

Finally, corridorisation reconfigures space, presenting it as smooth and frictionless, where the corridor acts as both a container and a channel for capital, resources, and people across scales (e.g. regions, states, and localities). Alff (2020:816) suggests that corridorisation conceptualises space as “intentionally broad and open, and at the same time, flexible and contingent”. Much literature on spatial reordering considers corridors at national and transnational scales (Lamarque and Nugent 2022). The economic potential of development corridors then relies on rendering corridors “marketable” by “smoothing” space—reducing the friction or barriers to flows of capital, people, and goods. By enclosing and opening certain geographical limits, corridors direct the movement of these flows, often at the expense of pre-existing social relations, as they, for instance, channel investments in infrastructure, zoning technologies, land concessions, and industries such as mining and agriculture. Spatial reconfiguration enabled by corridorisation is made legible through interdependent material and discursive processes. The processes of producing and arranging the corridor hide, rearrange, and sometimes hinder existing social relations, prioritising what is relevant to capital and what is not. As Thame (2021) suggests, corridors are not merely a “fix” for capitalism’s crises; they also exacerbate class struggle and exploitation, particularly through an extractivist paradigm. In the following section, we explore how the processes of enclosure and opening affect everyday life, tracing how the fetish of the corridor dissolves or obscures the socio-spatial relations that do not neatly align with the capitalist imperatives they portend.

Corridor Enclosure: Land, Social Relations, and Livelihoods

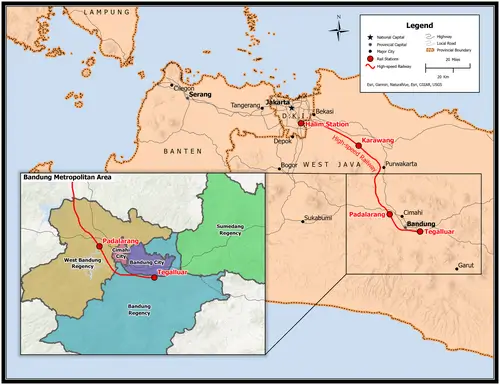

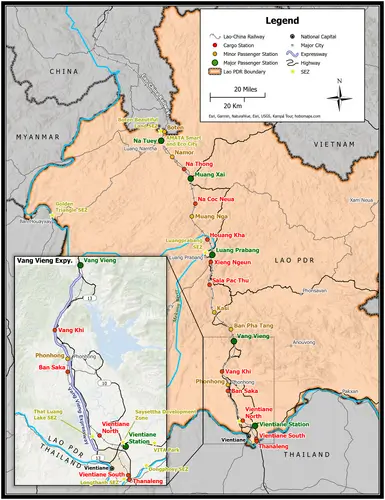

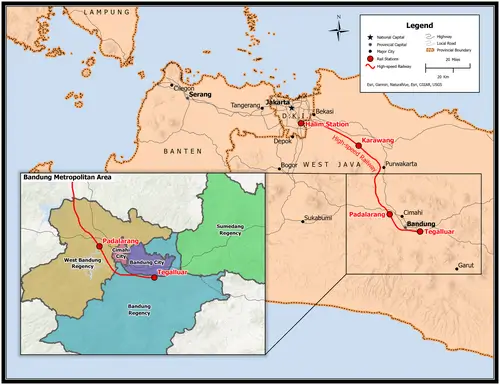

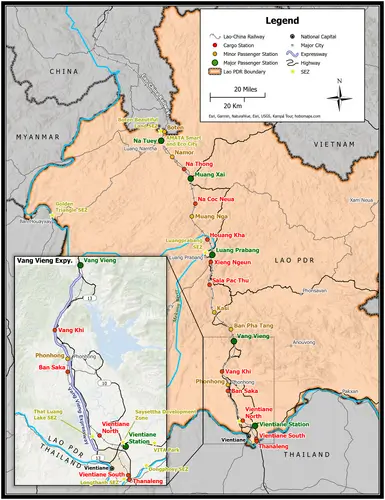

The Jakarta–Bandung Railway and the Laos–China Railway are linked to larger infrastructure and economic development initiatives, including the BRI. Both projects, significant Chinese investments in Southeast Asian infrastructure, promise reduced travel times, increased trade, and economic development. The Indonesian project, a 142 km railway designed for speeds up to 350 km/h, is part of the Indonesian central government’s infrastructural ambitions that entail many notable projects throughout the country (Hudalah et al. 2024). The high-speed railway aims to increase connectivity within the Jakarta–Bandung Corridor, generate economic development (Hudalah et al. 2024:300; Shatkin 2022; see also Nath and Raganata 2020), and generate further opportunities for investment from China and other sources (Salim and Negara 2016). Figure 1 illustrates the new connections established by the railway between Jakarta and Bandung, with railway stations notably situated outside the urban core of Bandung City, within the larger Bandung Metropolitan Area. Similarly, the 414 km Laos–China Railway, which spans northern Laos and is a component of the China–Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor, is a key project for economic development and connectivity (World Bank 2020). The railway connects Vientiane to the Chinese border and integrates passenger and freight transport with other large-scale infrastructure projects, including the Vientiane–Vang Vieng Expressway, eight Special Economic Zones (SEZs), and multiple large cargo stations and inland ports (Figure 2). In both corridors and the maps below, research site locations are not specifically identified to protect the anonymity of our interlocutors.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Map of the Jakarta–Bandung Corridor and high-speed railway in Java and Bandung Metropolitan Area (map by Trey Olson)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of the Laos–China Corridor, including the railway line and stations, main roads, and special economic zones (map by Trey Olson)

While the abstracted visions of smooth movement and development are compelling, our analysis highlights the uneven development underlying corridor imaginaries. These corridors are more than large, top-down political and economic projects. While they exemplify strategies to enhance regional connectivity, they also have far-reaching economic, social, and political ramifications within host countries. Their construction entails the (at times incomplete) enclosure of land, social relations, and livelihoods necessary for their longer-term development. Corridors rely on both realised closure and the potential for closure to create the seamless, integrated space they promise. However, the incompleteness of enclosure creates conditions that limit the corridors’ ability to fulfil their economic and logistical ambitions. This section examines three processes of enclosure, focusing on what is obscured in the construction of smooth corridor spaces. By centring lived experiences within development corridors, we challenge “infrastructural orthodoxies” (see Gurung 2021) that conceal the grounded and, at times, insidious effects of infrastructure.

Land

Corridor development begins with the enclosure of land. Land rights are often subordinated to national development goals, and existing socio-spatial relations are reconfigured to accommodate corridor plans. This enclosure process requires state and private actors to acquire and accumulate land to build the infrastructure that forms the circulatory system of the corridor. In both the Jakarta–Bandung and Laos–China corridors, this process entailed land demarcation and valuations to quickly acquire land while minimising costs for the state and developers.

In Laos, enclosure via land acquisition occurred through a protracted multiple-stage process. While a joint venture was established to oversee railway construction, the Lao government, primarily at the provincial and district levels, conducted all land acquisition and compensation through designated committees (see Suhardiman et al. 2021). State-led land compensation mechanisms sought to minimise the exchange value of land to make it available for railway construction and investment. Land was often appraised and compensated arbitrarily through inaccurate calculations, mappings, and observations, as the government lacked sufficient capital to meet its committed obligations for the railway. This undervaluing and under-compensating land reduced the government’s financial burden while accelerating corridorisation by making land available for immediate construction and future investment. However, this approach left many residents living along the railway in a prolonged state of precarity and suspension through, for example, displacement and inadequate compensation (DiCarlo 2024).

In the Bandung Metropolitan Area, the railway passes through the community of Desa Gancang,1 displacing many residents and creating long-lasting disruptions in their lives. The land acquired in Desa Gancang 1 fell into two categories: land owned by individuals and land owned by the state-owned enterprise PT Kereta Api Indonesia (PT KAI), one of several state-owned enterprises (SOEs) comprising Kereta Cepat Indonesia China (KCIC), a consortium of Indonesian and Chinese SOEs that own and operate the high-speed railway. Compensation for displaced residents varied dramatically depending on their land tenure. Those living on PT KAI land received 250,000 IDR/m2 (15.60 US$/m2) for their structures but not the land itself. 2 This rate is consistent with other cases, such as in South Jakarta (Sari 2017), where a 2013 PT KAI Board decision established that residents on PT KAI land with permanent structures would receive 250,000 IDR/m2 for compensation and those with semi-permanent structures would receive 200,000 IDR/m2 (12.58 US$/m2). In contrast, residents who owned their land received substantially higher compensation; for example, a participant reported to have received 1,750,000 IDR/m2 (109.23 US$/m2).

Compensation rates for land were significantly lower in Laos. A Chinese construction company boss explained, “Villagers will receive about 41,000 kip [4.55 US$/m2] for centrally located paddy or upland rice fields and about 20,000 kip [2.22 US$/m2] for land near roads”. These rates were often too low to allow displaced people to purchase new land. One woman in rural Vientiane province explained, “Our family has already been compensated for our house that was damaged and some of the cost to move, but I do not feel satisfied with the money they provided; it was 2,500,000 kip [275.00 US$]”. This amount was less than she had paid to build her house, and it was not enough to buy new land and rebuild.

Socioeconomic status and government connections influenced the compensation systems in Laos and Indonesia. For instance, poorer households outside Vang Vieng Station received as little as 17,000 kip/m2 (1.90 US$/m2), while a woman in Luang Prabang province who lost 2.5 hectares of lowland fields was told that land near a road would be compensated at 7,000 kip/m2, while land further from a road would receive 5,000 kip/m2. In contrast, more powerful households secured rates as high as 240,000 kip/m2 (26–27 US$/m2), similar to those who lived on PT KAI land in Indonesia but significantly lower than compensation for landowners in Desa Gancang. While the government purchased land at state rates, affected citizens could only find new plots at “market rates”, which were far higher.

In both Indonesia and Laos, project displacement had far-reaching social and economic consequences. Displaced residents often found it difficult to purchase land, rebuild, or reintegrate into their communities. In Desa Gancang, for example, residents did not relocate to one centralised area but dispersed across multiple locations, making it challenging to track or assess the full scope of displacement. Moreover, certain consequences cannot be quantified, such as losing emotional ties to one’s home. One resident, Bayu, recalled, “At first, many were mad because this is their home … their hometown has been destroyed”. Others were more resigned, feeling there was no alternative given the project’s perceived importance for national development. A Lao woman echoed this similar sentiment, “I am only an ordinary person; if the government already decided, we have to follow … I feel I do not have rights”.

Despite differences in land systems—Indonesia’s pluralistic land ownership versus Laos’ state-controlled land system—the processes of land enclosure in both countries shared key characteristics. This first phase of enclosure was not only about acquiring land for construction but also about transforming the land into a commodity to render the corridor “investable” by creating new sources of exchange value through residential and commercial development. Whether directly tied to investment projects or used for the railway infrastructure, land enclosure processes in both cases caused long-lasting impacts on the social relations of the community, a second form of enclosure we examine.

Social Relations

The disruption of land rights, use, and access, along with displacement caused by corridor development, also deeply impacted socio-spatial relations within communities. In Desa Gancang, residents were closely connected through family and neighbourly bonds in a densely populated village. The destruction of their homes and the forced relocation led to a breakdown in these social ties, with many residents scattering to different areas. Residents continue to feel the loss of social ties that have been disrupted, reworked, or severed after the land enclosure and construction of the railway. Nakula, a resident, reflected on his experience and the impacts on those not displaced, “After the project occurred, people moved everywhere. Examples like this lead to isolation. So, house A with house B, their socialising was tightly united. Now, it is somewhat tenuous”.

This experience of isolation was not solely caused by physical displacement; the changes to the built environment due to the railway have also contributed to damaging social relations. As a result of these changes, Nakula was forced to socialise in a new village and lamented that his social connections were stronger before construction. Later, when discussing community social relations, his son (in his early 20s) reiterated the railway’s adverse effects, describing how the community had been more densely populated with food stalls along the streets where he and his friends would spend time. However, such activities have significantly decreased as people moved away and fewer food stalls lined the streets.

In parts of Laos, the social impacts mirrored experiences in Desa Gancang. People were displaced, social relations disrupted, and villages disconnected. In Vientiane Province, railway tracks divided villages, separating households from their community. The new track made travel more difficult, as residents had to take detours or longer routes to reach town or neighbouring villages. Journeys to town that once involved crossing a dirt road now required motorbiking several miles down the tracks to a safe and permissible crossing, then retracing the journey on the opposite side. One resident described their increased fuel costs, which led them to visit towns or other villages less frequently. Additionally, social relations were disrupted in everyday tasks, such as caring for children, tending to animals, and maintaining close-knit community bonds, as some residents lost easy access to neighbours.

Construction also affected burial sites, an important aspect of social and spiritual life, with residents in both Laos and Indonesia speaking to the displacement of gravesites. In Desa Walungan, 3 where a cemetery was relocated due to the project, Dewi explained that the new cemetery was far less accessible, requiring a good car to reach it, whereas the old cemetery had been within the community. Similarly, in Laos, the removal and relocation of gravesites reworked inter-village social relations, particularly along the lines of ethnicity. For example, local Hmong villagers refused to move gravesites for fear of negative consequences, such as health ailments, for one’s family. As a result, members of the Khmu ethnicity were hired to relocate Hmong graves, foregrounding the corridor’s potential to exacerbate existing differences or create new ones. The disruption of burial sites not only affects the spiritual and cultural aspects of communities, but also has consequences for the social fabric that connects different villages. Smooth corridor space that prioritises efficient transportation and economic growth does not map neatly onto the preexisting social fabric of these communities.

Labour and Livelihoods

A third form of enclosure involves labour and livelihoods, creating new economic opportunities while simultaneously marginalising existing local activities. Corridors are intended to herald the arrival of capitalist forms of development that will “improve” and transform local economies through several economic goals, including the seamless integration between points of production and consumption, improved mobility of people or goods (Lesutis 2020; see also Enns 2018), and also local and regional economic expansion (Scholvin 2021). Such promises of economic growth and job creation were closely tied with the railway projects. However, what forms of economic growth; who is employed; and when they are employed are important questions to consider when analysing the effects of corridorisation and the projects that facilitate their development. According to participants, many employment opportunities in the construction phase were temporary and low-skilled. Local construction jobs on the railway tended to be manual labour, while other engineering, construction, and managerial roles were reserved for Chinese workers. In Laos, even though contracts stipulated that 30% of the workforce be local, the influx of foreign workers limited the availability of jobs for local people, particularly in higher-skilled positions.

The railway has been operational in Indonesia since October 2023; however, few, if any, residents of Desa Gancang are employed by the railway project. In contrast, residents of Desa Walungan have found employment at Tegalluar Summarecon Station or have found new sources of income in ancillary sectors connected to the railway, such as rental housing. However, the benefits for those living in Desa Walungan are not universal. Residents in both villages have reported dissatisfaction with their job opportunities. For example, station-related employment is restricted to people who meet certain age and educational qualifications, which residents described as roughly 30 years of age and a high school education. Additionally, in both villages, it was not uncommon for residents to lament the changing economic conditions in their communities as the railway project foreclosed their ability to continue their previous livelihoods, such as informal sellers or farming. Without access to former livelihoods, corridor-related jobs, or economic activity spilling into their village, many residents rely on factory work and informal sectors, such as food stalls, small stores, and short-term construction projects. However, much of this work is often temporary or contract based, with factory work often requiring connections or the ability to pay a fee to obtain a job. Therefore, it was common for participants to share experiences of economic insecurity and pessimism about the railway project. Cahya, who operated a food stall and had to move for the project, reflected on their current economic circumstances, “It is negative. There is no income at all”. Another food stall owner noted, “Before there were food stalls here, it was lively. Now, there are fewer buyers”. These changing economic conditions highlight the uneven distribution of benefits from the corridor, as certain livelihoods were no longer viable in the corridor economy to make way for more capital-intensive forms of development.

Those with the necessary skills, capital, and connections were better positioned to participate in the corridor economy, while marginalisation is exacerbated as ethnic minorities, women, less educated, and the poor often face additional barriers to benefitting from large development projects, raising concerns about whether corridorisation entrenches or exacerbates social and economic exclusion. In Rippa’s (2020b) words, “By speeding through territories, economic corridors exclude—rather than include—local communities from many of the benefits promised”. As a result, corridors produce uneven mobilities that shape who is able to benefit from development (Enns 2018). In Laos and Indonesia, the railway corridors facilitate the movement of goods, capital, and skilled labour while simultaneously constraining the mobility and livelihood opportunities of less privileged segments of the population. This selective mobility reinforces power asymmetries and creates new forms of dependency and vulnerability for those left behind by the corridor economy. For instance, a small-scale fruit farmer in Laos lost the few hectares of land that served as her primary source of income when it was expropriated for corridor construction. Losing this land meant losing her livelihood, and because she could no longer grow fruit to sell, she had few opportunities to benefit from the corridor economy.

The changing built environment has had significant impacts on local businesses, food vendors, and small stores that once thrived before the construction of the railway. In Vang Vieng, Laos, for instance, the railway has spurred a shift in tourism and the development of more upscale hotels in what was previously a small riverside town. As a result, local tourism offices have had to pivot their target audience, with several failing to adapt and subsequently closing. The forced displacement of communities in Desa Gancang for the high-speed railway disrupted local social life and economic activities by displacing residents and demolishing shops, harming local commerce. Food sellers reported a significant decline in customer traffic after the project began. For locals, the demolition not only eroded economic opportunities that existed before but also fractured the sense of community and social cohesion without offering alternative livelihood opportunities.

These shifts in livelihoods and labour possibilities highlight the need to understand corridorisation as a dialectical and often contradictory process that relies on multiple forms of enclosure. It often neglects or dispossesses locals that are directly impacted by these projects, at times in the form of slow violence and others through more coercive and exploitative measures. These processes are neither smooth nor devoid of resistance from those directly affected. However, in each case, local governments tasked with facilitating these nationally strategic projects often limit the potential for local agency, effectively marginalising their ability to shape the direction of top-down projects (Hudalah et al. 2022; Suhardiman et al. 2021). Yet, there have been notable instances of local resistance to the Jakarta–Bandung high-speed railway project, such as protests led by the Indonesian Forum for the Environment (Wijaya 2024; see also Weng et al. 2021) as, for instance, locals received compensation for damages to their homes, environmental degradation, and pollution resulting from the project. In Laos, residents who lost land also voiced their grievances, albeit in more subtle ways, such as repeated phone calls to local officials or speaking out during community meetings. However, many had little choice but to endure and wait for the promised land compensation (DiCarlo 2024). Despite friction and local pushback, enclosures occurred with an eye toward future investment. Indeed, the point of these multiple enclosures is to “open” the corridor to capitalist development, which we examine in the following section as enclosures render the corridor a legible space, itself commodified to attract speculative development.

Corridor Opening: Legibility and Speculative Development

Despite their flaws and failures, development corridors continue to proliferate globally because the process of corridorisation “opens” spaces to development and investment. To facilitate movement and capital accumulation, corridor space must be perceived as frictionless; thus, the corridor’s economic potential is tied to constructing an abstract and legible space. In addition to the material transformations enclosing land and lives, the creation of corridors as smooth, frictionless spaces open to investment requires discursive work to render the corridor legible to investors. This section first shows how corridors are discursively made legible and second identifies the effects and investment outcomes of that legibility.

Legibility

Constructing corridors as commodities “open” to investment and capitalist development involves creating narratives of opportunities to attract capital to render the corridor legible to investors. This legibility is crucial because it assembles the necessary components—land, labour, capital, and expertise—in ways that make a particular development project attractive to investors (Li 2007). For corridors, this entails the physical transformation of space and the discursive construction of the corridor as a site of economic opportunity. In this sense, corridorisation is not just about infrastructure; it also involves the construction of a particular vision or spatial imaginary that presents the corridor as a potential economic hub (Aalders et al. 2021). Enclosure creates the conditions for investment, integration between sites of production and consumption, and seamless movement while planners and developers produce a coherent, legible vision of the corridor’s potential. This vision is presented through plans, investment brochures, and promotional materials that depict the corridor as a space brimming with economic promise. This is also achieved through material processes like standardisation, quantification, and simplification, all of which attempt to smooth over socio-political complexities. Creating the corridor as a legible commodity was essential for articulating the conditions that would generate returns for public and private investors and justify corridor projects.

For example, in Laos, investment brochures and promotional materials 4 emphasise natural resources, strategic location, additional infrastructure, and investment opportunities. The corridor is consistently described as traversing “resource-rich regions” with “untapped” mineral deposits and fertile land for mining and agribusiness (World Bank 2020, 2022). It is also positioned as a “crossroads” or “gateway” to Southeast Asia, poised to capitalise on growing regional markets. Beyond the railway, roads, cities, logistics hubs, and SEZs promise to unlock the region’s economic potential. Similarly, in Indonesia, transit-oriented development (TOD) was envisioned to promote frictionless movement between residential communities, commercial spaces, and other urban developments, as well as Jakarta and Bandung. One TOD project was conceived as an environmentally friendly, mixed-use space to foster sustainability while delivering financial returns. The design conjured a utopian green future, reflecting the growing global trend of environmentally oriented economic growth. The narratives produced to make corridors legible are designed to generate excitement among investors, policymakers, and the public by offering a clear, orderly vision of inevitable progress. Yet, such discourse glosses over the tensions and frictions involved in transforming these spaces. Although these utopic imaginings have yet to materialise within Laos or Indonesia, they were vital to getting projects off the ground. As a result, processes of rendering development investable often mobilise speculative futures and anticipatory logics to attract investment and justify the corridor’s transformation.

We identify three forms of future-oriented investment that emerged alongside these corridors as investable commodities: Transit-Oriented Development (TOD), Special Economic Zones (SEZs), and competitive speculation. TOD is viewed as a development model that can promote inclusive growth and sustainability by reducing reliance on vehicles (Federal Transit Administration 2025). However, in Jakarta, TOD has produced uneven development because it is a form of speculative urban development that makes the city less accessible for most of the population through increasing housing prices and pushing people off the land (Anguelov 2023). While SEZs are framed as “engines of development”, they also lead to speculative and exploitative practices. Finally, competitive speculation arises as domestic and foreign actors vie for investment opportunities once the corridor becomes legible. In what follows, we turn to these forms of anticipatory development.

Trends Toward Speculative Development

Corridorisation, beyond connectivity, is concerned with wider-ranging, large-scale developments and investment. It produces a commodity fetish that obscures the violent and incomplete processes of corridor enclosure to emphasise future accumulation potential. Across Southeast Asian railway corridors, we have been struck not only by the newfound connectivity but by the emphasis, particularly by planners, officials, and investors, on “upgrading” corridor space to mirror the new high-tech railway systems. Three trends in future-oriented investment have emerged in response to constructing the corridor as a commodity: TOD, SEZs, and competitive speculation.

First, TOD has become a favoured urban development approach in Indonesia, despite limitations in achieving lofty aims of integrated transit, sustainability, and economic development. It remains a seductive development idea that taps into broader development discourses, like sustainable development. However, as Citra, an urban designer, pointed out, TOD often serves as a “gimmick” to generate enthusiasm for development, particularly in cities like Bandung, which “already had good transportation, but not very structured. It was working well … But all of a sudden, there is KCIC, and everybody talked about TOD”. TOD and related capital accumulation became crucial for the economic justification of the high-speed railway and reimagining the city’s future. One estimate suggested that TOD could generate US$18.6 billion in revenue by 2070 (Mufti 2019), far exceeding the initial cost of the railway (US$5.5 billion). However, this estimate was made before the postponement of Walini Station, which Padalarang Station replaced as one of the four initial stops (Kereta Cepat Indonesia China 2021). Surbana Jurong (2024), a Singapore-based consulting group that worked on Walini Station TOD, described it as a means to “optimize land use and improve the social and economic status of the surrounding regions. It is expected that this effort will produce a model for a liveable and sustainable TOD to support integrated transportation for the country”. In a conversation on TOD’s role within the railway project, a KCIC employee explained, “If we [KCIC] only rely on ticket revenue, it is insufficient to cover all the operational costs for the high-speed railway. That is why the initial planning needs TOD development”. Together, the railway and TOD promised to improve connectivity and prioritise large-scale urban property development to create massive returns for private and public actors.

However, actual TOD has been limited in the case of the railway corridor. According to the same KCIC employee, the company faced challenges in acquiring and developing land for TOD, attracting investors, and navigating regulatory hurdles. Rather than implementing the earlier plans for TOD, KCIC established relationships with preexisting mixed-use communities near the stations, particularly the exclusive middle-to-upper-class residential and shopping areas. Even if the TOD plans have not been realised, this development ideal persists and influences urban development. Former President Joko Widodo reiterated the role of TOD during the railway’s inauguration, “the Jakarta–Bandung High-Speed Railway marks the modernisation of our public transportation, which is efficient, environmentally friendly, and integrated with other modes of transportation, as well as its integration with TOD” (Sekretariat Kabinet Republik Indonesia 2023). The importance placed on TOD within the railway corridor highlights how framing development corridors as investable commodities through abstraction can overlook the tensions between these abstractions and complex socio-spatial realities. TOD and other speculative development projects in development corridors continue to be enticing because of the power found in their discursive simplicity. Yet, the abstraction of the actual conditions in which these projects are meant to materialise can contribute to the incompleteness of development corridors.

Second, corridorisation and increased legibility have also spurred speculative investment through SEZs. A Vientiane Times (2018) front-page headline about the Laos–China Corridor declared that the railway would “open doors for the establishment of SEZs” to attract and diversify foreign investment and reduce reliance on natural resources. Corridorisation in Laos has reinvigorated SEZ development, including Vientiane Logistics Park, Saysettha Development Zone, and Boten Beautiful Land, among others (see Figure 2). SEZs have been newly proposed and revitalised, designed to attract investment in logistics, manufacturing, and tourism sectors. These zones rely on improved connectivity from the railway to position themselves as attractive investment opportunities. For example, Boten SEZ and Luang Prabang SEZ are located near main railway stations and have seen a boom in investment due to the corridor. Based on an interview with a representative from Phousy Group (the developer of Luang Prabang SEZ) as well as project documents they shared, the company sought US$1.2 billion in investment for real estate, a hospital, a golf course, a stadium, shopping centres, infrastructure, and more. As of 2023, a five-star hotel is under contract. However, construction of the SEZ has yet to break ground. Developers also rely on Luang Prabang’s UNESCO World Heritage site status to draw in capital. Yet, because of this status, the SEZ is proving challenging to expand to the extent initially envisioned and, instead, is so far limited to the already dense tourist centre.

In contrast, Boten SEZ, a 1,640-hectare zone near the Laos–China border, is rapidly developing, with plans to create housing to accommodate up to 350,000 residents by 2035, along with investments in agriculture, manufacturing, and tourism (DiCarlo 2022). The Chinese developer has a US$10 billion, 15-year construction plan to build a new international city at the railway’s “first stop” in Southeast Asia (ibid.). Other investments include agriculture, livestock, manufacturing parks, a cultural centre, a five-star resort, a tourism zone, and a logistics area. In the meantime, according to interviews with the Boten sales team, the company is seeking investors for various projects and businesses, and has begun to sell apartments. Unlike Luang Prabang SEZ, which seeks investors through development plans, Boten SEZ is a small city with growing construction. Investors and businesses visit the sales centre in the zone and are presented with a model of the city and tourism areas they might invest in. This SEZ revitalisation demonstrates how the corridor has become a legible space for investment from Chinese investors to Lao and Vietnamese businesses and global corporations. The fetishisation of the corridor enabled planners, companies, states, local authorities, and international institutions alike to pursue infrastructure projects and investment agendas, engaging in speculative development based on the corridor’s newfound exchange value.

Finally, corridorisation has led to a third form of opening based on increased investor competition. For instance, in Laos, a Chinese company spearheaded the development of a large SEZ, only to find that another developer co-opted its plans. On a summer day in Vientiane, the first author sat in an upstairs restaurant with members of a Chinese SEZ team. They had come for their regular meeting with Lao politicians to “smooth out” issues, usually by paying various fees to continue construction and maintain relationships. These pivotal meetings had become even more pressing in recent years after a Thai developer with high-level Lao government connections co-opted one of their projects. One of the team members grumbled, “We shared the city plans with [the Thai developer] in 2016 … Then, they stole the entire plan and presented it as their own. We could not fight with the Prime Minister’s office, so we lost that plan even though we did all the feasibility studies and planning”. An official at Lao’s Ministry of Planning and Investment later explained they wanted a Thai project next to the large Chinese one, noting that “It cannot be all Chinese. In Laos, we need balance and investment from many countries”. At the same time, companies from Laos and other countries have been eager to engage in the space, using the Laos–China corridor to cite a need to ensure that “it does not become Chinese”. This competition highlights how the corridor’s subsequent enclosure and opening motivate actors to vie for control and influence over lucrative projects, leading to geopolitical manoeuvring and investment competition. Additionally, corridorisation motivates engagement where it would otherwise be overlooked or unnecessary. For instance, international organisations also compete for corridor space, deploying corridor language for poverty reduction. For example, a UN FAO officer requested all the first author’s information on the railway and corridor as they rushed to plan an initiative to “alleviate poverty and end hunger” using the “corridor as the development unit”. This was puzzling, as the corridor covers some of the least poverty-prone, most accessible parts of the country. Yet, corridor legibility, intended for investors, also shapes how other actors engage in the space. Various actors—from states to international organisations and companies—deploy corridor rhetoric to pursue investments, revealing how the corridor’s enclosure and opening are buried beneath the rhetoric of cooperation.

These trends reveal several important insights about the discursive and speculative dimensions of corridorisation, demonstrating how corridors are constructed as smooth, frictionless spaces of untapped economic potential to justify investment and large-scale transformations. Second, making corridors legible enables the commodification of corridors and encourages speculation and development by transforming complex spaces into seemingly straightforward investment opportunities. Third, the cases show how corridor projects are justified and driven by speculative visions of future returns like TOD and SEZs, which often promise returns far beyond the initial infrastructure investments. Corridorisation creates new competitive landscapes where various actors (investors, states, and international organisations) vie for influence and control.

As this section demonstrates, “enclosure-to-open” is a central characteristic of corridorisation that transforms places and people into commodities and investable assets. Yet the dangers of fetishising corridors as abstract spaces of frictionless development persist beneath speculation. The speculative dimension of corridorisation relies heavily on anticipatory logics, where future potentials are used to justify present actions and investments. This can lead to a cycle of ever-expanding corridor projects based on projected rather than realised benefits. Producing development corridors as a commodity may generate profit for investors but obscures the lived realities and frictions on the ground that do not fit within imaginaries of smooth space. If the railway is to uplift the economy and provide local benefits and opportunities, the fetish of the development corridor needs to be overcome, and the forms of development connected to corridors need to be reconsidered.

Conclusion

The logic of development corridors has become entrenched through a complex assemblage of policy networks, international agreements, and economic rationales. They create institutional inertia that sustains a perception of development corridors as a path for economic development despite evidence pointing to their limitations and unintended consequences (Dwyer 2020). The processes perpetuating development corridors are political and social, not merely economic. Lobbying efforts, public relations campaigns, and public discourse all contribute to normalising and accepting corridors as a standard development strategy. Narratives of economic growth and seamless integration are powerful for maintaining the status quo, even when lived realities diverge significantly from the idealised vision. Moreover, the ongoing capital flows and investments in development corridors create a self-reinforcing cycle, perpetuating a dynamic in which the promise of economic gains and development overshadow persistent challenges and adverse effects.

To understand these dynamics, we conceptualise corridorisation as a process of commodification that occurs through the abstraction of tensions between enclosure and opening and use and exchange value. As a dialectical process, it entails fetishisation that renders corridor space legible for certain types of investment, speculation, and uneven capitalist development. Viewing corridors as commodities highlights the power of the fetish that obfuscates the exploitative and, at times, violent realities while “buying and selling” the corridor through its visions of a speculative future. The reproduction of the corridor as a development technique relies on framing corridors as frictionless spaces while ignoring the violent and incomplete processes of enclosure necessary to render them investable and promote an idealised development future. The material and discursive aspects of corridorisation are mutually reinforcing, and the process is made possible through the abstraction and fetishisation of the corridor as a commodity. Corridor legibility is not without contradictions. Simplifying and standardising the corridor obscures complex realities on the ground, including social and environmental costs. Furthermore, corridor development is speculative, so benefits may never materialise even as communities and investors bear the effects and risks.

By examining processes of corridorisation and tensions inherent within, we can better understand how land, labour, and capital are arranged to facilitate both enclosure and opening of corridors. The corridor undergoes a process of fetishisation that hides enclosure processes and dispossession to sell the image of frictionless space and capitalist hyperreality. This approach points to the socio-political effects of corridors and the possible points of contestation that can arise when abstraction comes face-to-face with complex local dynamics within and far beyond the corridor. It is essential to centre such tensions, contradictions, and dynamism, especially as corridors fail and are revitalised with new sources of investment. Recognising these dynamics is crucial for understanding the complex and often contradictory nature of development corridors, their implications for communities and regions, and which interests they serve. In sum, development corridors, while framed as transformative development solutions for economic and spatial challenges, are shaped by the dialectics of enclosure and opening, abstraction and fetishisation, and use and exchange value—processes that obscure their uneven, incomplete, and often violent impacts, ultimately reinforcing the contradictions of capitalist development rather than resolving them.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jacob Henry and two anonymous reviewers for excellent feedback on this paper, the editors at Antipode, as well as Emily Yeh and Tim Oakes for their invaluable mentorship over the years. Additional thanks to Emma Loizeaux, Shae Frydenlund, Fan Li, Tsering Lhamo, and Phurwa Gurung, who offered feedback on early iterations of this research within a graduate student reading group. We are thankful for M. Ekazaki Kurnia’s inestimable and tireless support in Indonesia and several research assistants in Laos who cannot be named. Thank you to Trey Olson for designing the maps for this article. Finally, we thank the following organisations for their research funding and support: the Fulbright US Student Research Fellowship, the University of Colorado Boulder, the Association for Asian Studies, the Asian Geography Specialty Group of the American Association of Geographers, and the Center for Development and Environment. This research was approved within each author’s respective IRB. We have no conflicts of interest to report.

Endnotes

- A village pseudonym. In Indonesian, desa means village.

- Conversion rates from Indonesian rupiah and Lao kip to US dollars are based on the time of writing.

- A village pseudonym.

- Promotional brochures and materials were obtained only in hard-copy form by the first author from SEZ field sites.

Last Updated: Mar 18, 2025 @ 5:41 pm